Perhaps more so than any other sporting events, combat sports inspire confidence. Confidence, that is, in who is going to win a fight. Everyone thinks they know what’s going to go down once the bell rings. It is this confidence that makes the great matchups, the real nail-biters, so invigorating. Perhaps it is also why combat sports are so closely linked to gambling. After all, when Mike Tyson was at his prime, who could possibly beat him? Going into his first fight with Evander Holyfield, it seemed the bookmakers were selling dollars for 82 cents. And yet it was Holyfield who prevailed.

Fighting is random, probably much more random than other sports. In soccer, if one player is having a bad day, or is hungover or secretly injured, they have a whole team to pick up the slack. In MMA, there is nobody to pick up anything, and one bad night can dramatically alter a career. Not to mention that a single bad moment can end a fight immediately. So the question stands, people like to guess and bet on the outcomes of fights, and fight are unpredictable — how good are we at picking fights?

Tapology’s Data

Tapology is a website that collects and presents data on MMA fights, and combat sports section. Beyond that, they’ve nurtured a relatively robust user base with community content such as user rankings (who’s the greatest fighter of all time?), an active forum, and a system of ranking user’s predictions on fights. Tapology is an excellent website, and a really important resource for MMA fans (especially data nerds like myself). This last community feature, user predictions of fights, is what really interested me. Just how good are people at guessing fight outcomes?

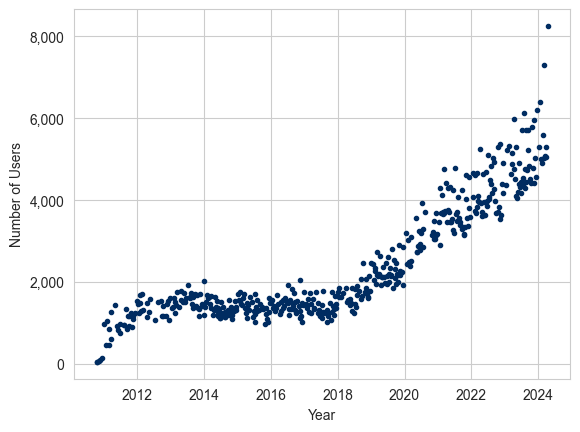

It’s important to note here that these predictions have been effectively gameified by Tapology, with users earning points and awards which eventually earn ‘belts’ for good predictions. This has nurtured a very active community, and some users have been submitting fight picks for years, numbering thousands of bouts. Overall, on UFC events, there are 1,146,671 total fight picks. This number has been picking up over the years, where by 2023, the majority of events had more than 4,000 picks.

So how good are they? Overall, Tapology users pick the correct fight ~63.5% of the time. So pretty good right? Well it’s maybe not as obvious as it seems. Lots of fights are essentially sure-things, big mismatches which you don’t need prescience to guess correctly. Think fights like Bo Nickal vs. some guy or Jon Jones vs. basically anyone at light heavyweight. To really evaluate how good people’s fight picks are, we need a baseline, something to compare them to.

The Bookies

Luckily for us, each fight comes with odds made by bookmakers. These odds imply a certain prediction about the likelihood of one outcome or the other. These predictions are based on so-called ‘fair odds’. That is, if the bookmakers were offering fair odds, odds such that the expected value of the bet was $0, what would the probability of the outcome have to be? For example, the fair odds on a coin flip would be 2-to-1 (or -100 in American odds). Then, with a 50% chance and a $100 bet, you’d win $100, and with a 50% chance you’d lose $100. So when a bookie gives odds like -250 (a moderate favorite), the fair odds probability would be ~71.4%.

Of course, bookies do not offer fair odds, otherwise they would not make any money (probably, it’s a bit more complicated than that). Bookies have the advantage of being able to provide predictions that do not add up to 100%. For example, when two fighters are expected to be about equal in skill, and the probability of one or the other winning is thought to be 50%, bookies will often give both fighters -115 odds, which translates to a probability of about 53.5%. Meaning they think that both fighters have a 53.5% chance of winning, which together add up to about 107%. That 7% is called their vig, and it guarantees (kinda) a profit for the bookmakers. So while a person is bound by the laws of probability to give predictions that add up to 100%, the bookmakers are not. This gives them an advantage in predictions that we do not have. The house always wins and all that.

But the nature of bookmakers is not solely directed in their advantage. First, while the inner workings of a bookmaker are opaque, they likely do not have the resources or the incentive to deeply analyze each fight that they offer odds on. Most bookies follow one another, and aim to be within the range of odds of other bookies. An obsessive fan, the type to make thousands of predictions on Tapology, almost certainly understands the fight better than the bookies. Second, and crucially, bookies are profit-making enterprises, not fight predictors. In reality, they don’t care at all about who wins a fight, only that they make a profit. Of course, accurately predicting fights can help them do that, but they are also beholden to the amount of money bet on each fighter. For instance, suppose that going into his fight with Khabib, it was well known that Conor McGregor had a 10% chance of winning. After all, Khabib is a dominant wrestler, and that has never really been Conor’s strong suit. But Conor is really popular, and has extremely loyal ride-or-die fans. So despite his uphill battle, maybe 50% of all the money bet on the fight is on Conor, not Khabib. Then, the profit maximizing odds for the bookmaker would be to make Conor something like a +2001 underdog, implying a 33.3% chance of winning, not 10%. That is, bookmakers are biased by their very nature, so long as people’s bets do not align with the true probability of an outcome.

Who’s Better?

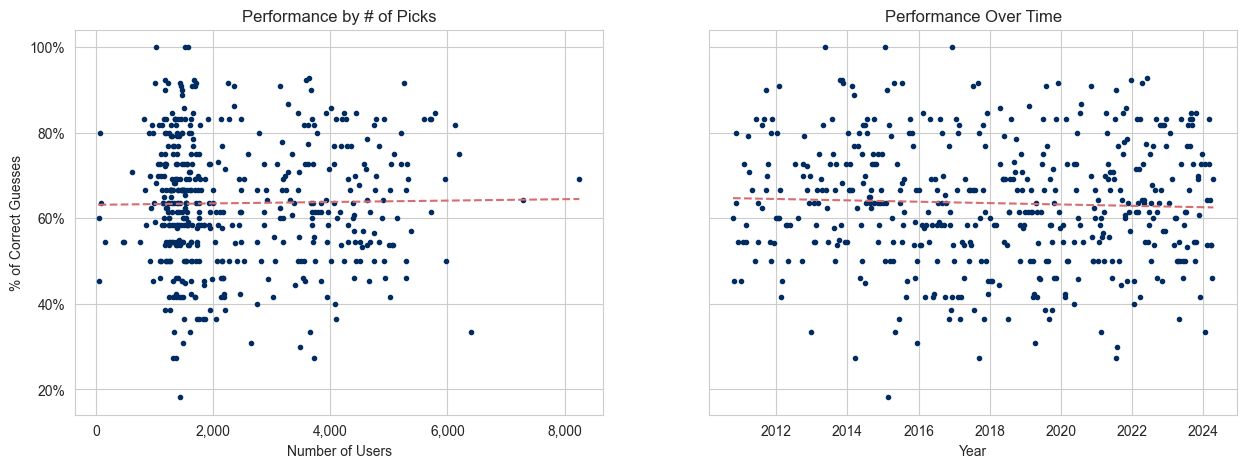

The bookies have some clear advantages picking fights, but maybe also some disadvantages. So the battle is on, who is better, the people or bookies? The answer is disappointing — the bookies. While Tapology users predict fights at a ~63.5% clip, the bookies accurately predict about 65% of fights. But let’s dig into this a bit more. Maybe this is the result of old picks, maybe people are getting better over time. Or maybe there are better predictions when there are more fight picks on a card.

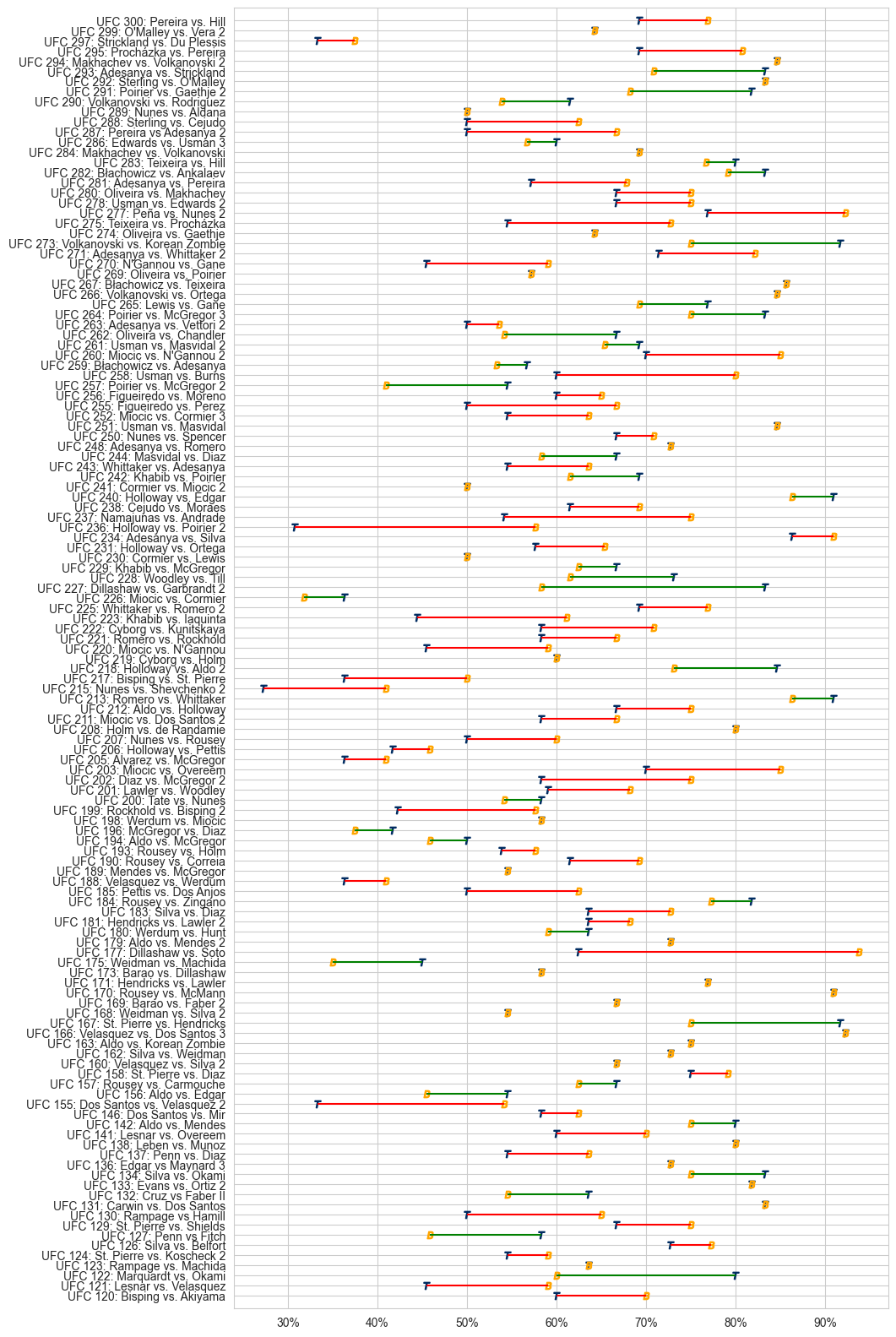

Nope! There seems to be no real correlation between either time or the number of picks. Let’s look at the data on an event-by-event basis. The graph below shows the relative performance of bookies and Tapology users for numbered UFC events. There is a green bar where Tapology users outperform the bookies, and a red bar otherwise. Here the performance of Tapology users is a blue “T” and bookies are an orange “B”.

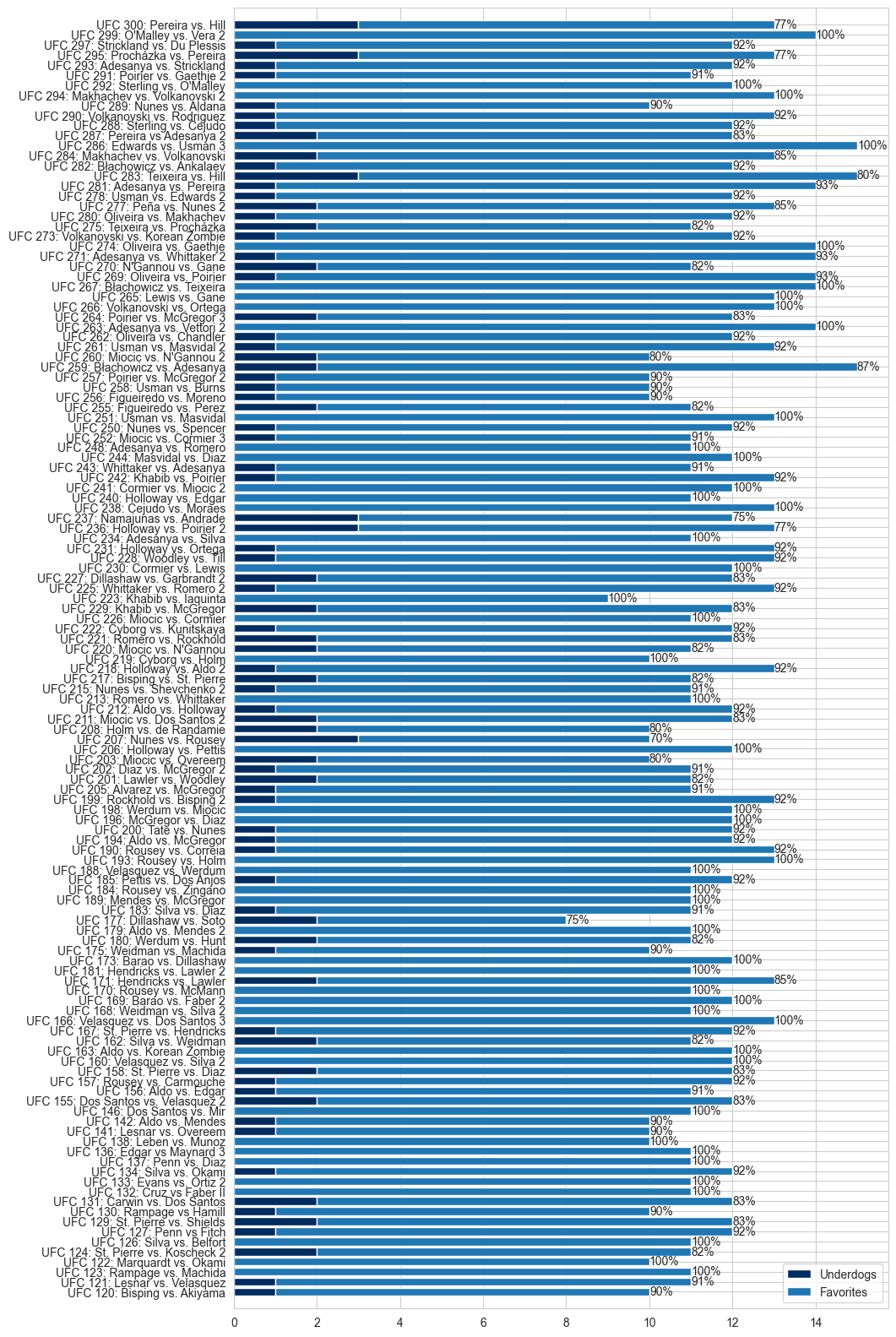

Looking overall at the numbered UFC event, the results are pretty dismal. Most times, the bookies outperform Tapology users, and there are lots of ties. There are some bad ones. For instance, users only picked about 20% of the fights correct for UFC 236. Yikes! But maybe things aren’t as bad as they seem. Perhaps it is the case that users are bad at picking favorites, but good at picking the riskier underdogs. Are users and the bookies generally picking the same fights (i.e. favorites), or are users being more risky, choosing underdogs? The graph below shows the number of favorites and underdogs picked by Tapology users. The numbers on the right the total percentage of favorites picked.

The reason then is clear, it seems that Tapology users are, generally speaking, picking betting favorites to win. Of course that makes sense, but how could users possibly hope to best the bookies by picking the same fights?

Conclusion

So do we just suck at picking fights? Does this extend to other places, are people just bad at making estimates of random outcomes? Maybe not. Surely it seems that we and bad at picking fights, but it might still be the case that you are good at it. The fact that a bunch of people’s pick does not necessarily mean that no one can pick, just that most people can’t.

Who really cares? At the end of the day, this is just picking some fights for fun, it doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things. But this is an example of a larger phenomenon, sometimes called the ‘Wisdom of the Masses’, the idea that by collecting predictions or responses from a large group of people you can get better estimates than by polling one or just a couple of people. It’s the premise behind lots of things, including using sentiment analysis to pick stocks, or price setting mechanism in public markets generally. In fact, there is a lot of research (Fietcher and Kornell, 2021) that in experimental settings, this effect works well.

So why doesn’t it work here? Why is it that with over a million predictions, they don’t turn out so well? There could be a few reasons. First, people might pile on estimates that they are sure about, big favorites that are all but guaranteed, and shy away from making risky estimates (i.e. underdogs). In situations, such as this one, where there are incentives to get correct estimates, people may avoid picking unlikely but possible outcomes. While this situation is explicitly gameified, with users getting points for correct picks, many similar scenarios, such as stock markets, also provide significant incentive (i.e. profits) for getting things correct. Second, this is not an experiment with tightly controlled information, and everyone here sees what odds the bookmakers are offering. That is, there is a big giant signal to everybody about the true probability, and that may influence people’s thinking about a fight. To again use the example of the stock market, the price of a stock today provide a powerful signal of it’s underlying worth that is likely to influence people.

While our intuition and academic research tell us that more data points, more consensus is invariably better, in the real world it is not so obvious. When trying to predict an uncertain outcome, beware the wisdom of the masses, because everybody has access to the same information you do, and not everyone knows quite what to do with it.

Assuming a 5% vig